By Ian Kennedy

Contemporary popular debates about race and racism are caught in a difference of assumptions. On the one hand, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article “The First White President” in the October 2017 issue of The Atlantic exemplifies the systemic view: white supremacy and racism are perpetrated by all members who share a particular identification, leveling racist violence on all members who share a different identification. To varying degrees, all white people contribute to white supremacy, and all non-white people are victims of this violence. For Coates, a pervasive identity of whiteness unites Trump and his supporters. In contrast, white journalists who responded to Coates, most notably George Packer in his September 15th response in The Atlantic, equate racism with bigotry. Packer, taking a cognitivist view of action, argues that white supremacy might describe the minds of some Trump voters, but is certainly not applicable to all whites. This narrative about racism usually deploys a simplistic mental test. Packer, I imagine, looks into his heart, sees no obvious bigotry, and thus labels himself not-racist. Coates and Packer face each other with disparate ideas of how racism and race affect action. Coates is focused on action aggregated into systemic oppression, Packer on individuals isolated from their context.

Yet the two views are not equal. Scholars of race have reached a theoretical consensus very similar to Coates’ view: racism is not a set of beliefs or values held by individuals, but rather an entity that pervades whole groups of people. Its pervasiveness is enacted with and without ideology. White supremacy, a particular instance of racism, denies the full humanity of non-white bodies. Focusing only on ideology, Packer sees white supremacy in some voters, but misses the white supremacist impetus that is intertwined with all white voters’ actions, regardless of how they cast their ballots. This article examines one reason Packer’s view, when compared to the systemic view, looks so distorted.

It seems as though Packer is unable to see the world in a way such that Coates’ systemic argument makes sense. Like many white folks, Packer’s view seems bewitched by older theoretical constructs that state racism is determined by ideology and held in the minds of individuals. The world shows up for him differently than for Coates and many modern theorists of race. This brings us to a remarkably difficult impasse. Packer and many other liberal whites, distracted by their view of their hearts as non-racist, cannot see white supremacy as a system that implicates them. That is not to say that Packer’s self-examination is insincere, and my argument holds regardless of whether he harbors racist beliefs or bears ill will towards people of color. But this gets us to the heart of his real mistake: he is enchanted by a particular theory of action which, because it is overly focused on individuals, masks the systemic nature of racism and white supremacy.

By reframing this debate in terms of theories of action, I offer an intervention which aims to both affirm Packer’s assessment of his mentality, but at the same time demonstrates the complicity of all white people in white supremacy. To do so, I reference the contemporary revival of a classic take on social action, called practice theory. While traditionally inadequate in areas of race, a revitalized practice theory can connect racism to the acts of oppression which construct it. I affect this revitalization by building on the work of Alexander Weheliye and Saidiya Hartman.

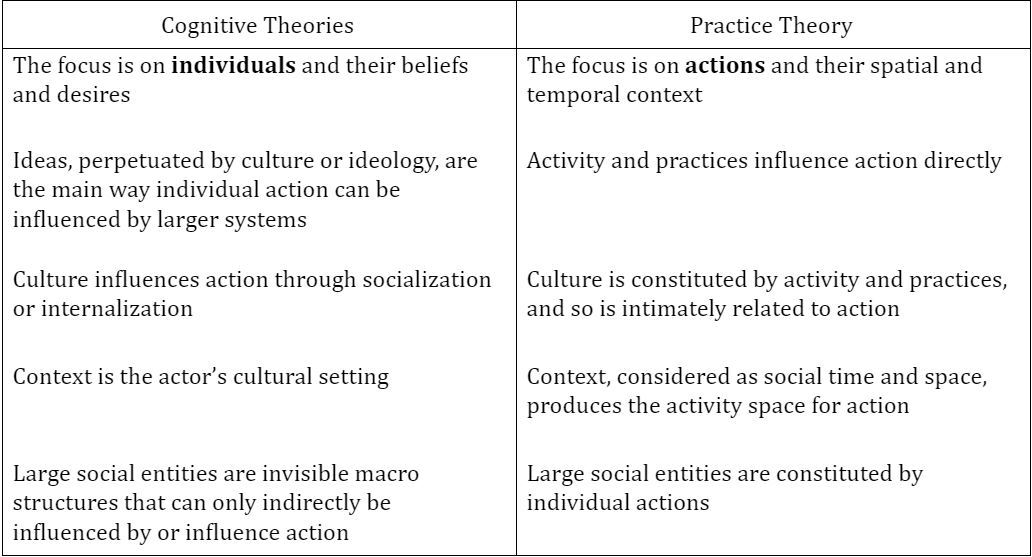

This, then, is a good time to outline the theoretical topology of the debate between traditional cognitivist theories, in which action stems from beliefs and desires held by individuals, and practice theory. Table 1 sketches these in broad terms. First, by focusing on actions instead of individuals, practice theory is less worried about whether someone or other is a racist person and instead with whether their actions contribute to white supremacy. Cognitivists rely heavily on ideational worlds, in the minds of actors and in culture, ideology, and discourse. This leads to the problem of how individuals internalize values or are socialized into culture. As leading practice theorist Theodore Schatzki writes, the account of the social that an examination of practice offers “contrasts with accounts that privilege individuals, (inter)actions, language, signifying systems, the life world, institutions/roles, structures, or systems in defining the social” (Schatzki 2001: 3). Practice theory affirms the importance of studying cultural and discursive forms, but argues that it is the organization of human action which directly influences subsequent action without recourse to discourse or verbal thought.

To make this claim, practice theory uses a different definition of social context. Instead of being simply a discursive setting for an actor, a shared space of opinions and beliefs, I construe social context is instead an enacted social space and time. That is, particular actions, like buying a bus ticket, are possible because of the enacted spaces and times which give the meaning “buying a bus ticket” to the specific action of exchanging twenty bucks for a slip of paper. No one is going to mistake such an action for bribery because of the time and space in which this action takes place. A bus driver in the 1920s might mistake your twenty dollars—an exorbitant amount at the time—as bribery, so might a bus driver where public transportation is free.

This is a fancy way of explaining how a well-designed door handle seems to ask to be pulled, or why it feels odd if a door with such a handle needs to be pushed. The action of opening a particular door is an instance of the activity of door-opening in general. This activity, in turn, forms a part of the human practice of entering and exiting a room. This practice is further interwoven with the practices of door construction and architecture, practices which are essential for forming the social contexts of time and space. The result is such that it feels instinctual for people alive now to push or pull on a door handle while the same handle would bewilder a person from the paleolithic era. Practice theorists call such a space and time-specific instinct ‘practical understanding.’

Table 1: Key differences between Cognitive Theories and Practice Theory

Practical understandings are connected to a last key advantage of practice theory over belief-plus-desire accounts that is particularly important when considering systems of oppression. Belief-plus-desire theories of action, partially because of their focus on individualism, have trouble connecting individual action and large scale social phenomena. That is, put generally, Packer’s problem in the debate with Coates: the cognitivist view does not account for how actions not motivated by thoughts of racism can contribute to white supremacy. Practice theory focuses on tracing how actions constitute practices and how practices form contexts for further action, as I sketched briefly with the examples above. Practice theorists love analyzing innocuous things like the interaction of door design, production, and installation with the practice of door opening. We are going to do something different.

Let us imagine two white men, similar in stature and weight, both from Ohio. They reacted differently to the election of 2016, but in the spring of 2017 both read about upcoming protests and rallies in Charlottesville, VA, and decided to buy bus tickets to go and participate. A cognitivist account would probably start with how each man justified his action through discourse and ideology, but such an account would end up offering no explanatory value beyond the experiences of the two individuals. A man who claims to honestly believe in racial equality attends the rallies under a sincere conviction that whites are being silenced in America, though he stands next to another man who wants to exterminate a racial group. A belief-plus-desire account does not even begin to explain how these two ended up together in Charlottesville. A practice theoretical account, on the other hand, discovers and brings into focus the white supremacist practical understanding intimately shared by the actions of both men.

Completing such an analysis requires more about the history of practice theory and race, and more detail about the working of practice theory itself. Most contemporary practice theory traces its roots back to Bourdieu’s Outline of a Theory of Practice, which, though published in 1977, continues to be a major touchstone. Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory, introduced in his 1984 Constitution of Society further developed the relationship between individual action and supra-individual structure. The best known contemporary practice theorist is Schatzki, whose 1996 Social Practices developed and made explicit the discipline’s connection to Wittgenstein. Schatzki’s influence has continued and his 2010 The Timespace of Human Activity both makes clear the phenomenological, especially Heideggerian, roots of practice theory while at the same time offering an account of social space and time as co-constitutive and integrated.

The more successful practice accounts to do with race are not written by practice theorists interested in race, but by historians, ethnomusicologists, scholars of literature, and others who bring practice theory into their diverse disciplines. Charles Orser wrote a detailed application of Bourdieu’s habitus to race in the discipline of archaeology (2013). Matthew O’Hara and Andrew Fisher used practice theory to frame their historical investigation of race in Latin America (2009). Guthrie Ramsey used feminist theories of practice to help outline his ideas about music in the black diaspora (2003). Hartman theorized the constrained agency of slaves by examining practices (1997). Finally, Sue Feldman and Ilana Winchester showed how a practice orientation could help design and implement education policy which could undermine institutional racism (2015). Taken together, these successes show the efficacy of bringing practice approaches to bear on diverse aspects of race theory and policy.

The above examples of practice accounts are all about race and power. What differentiates them from other approaches is that focusing on practices brings our attention to particular human actions. In the simplest way, practice theory points us back to what people are actually doing and constructs social structures from the ground up, in contrast to the top-down approaches which focus on ideology or discourse. This difference matters in theory and in practice, as Feldman and Winchester point out: “Emphasis on research designs not sensitive to the on-the-ground interactions, where (in)equity in education is happening in real time, constrains research findings” (2015, 65). By using a practice approach, theorists not only gain sharper methodological resolution, but also open the way towards better strategies in hospitals, schools, and organizations.

O’Hara et al. gather those “on-the-ground interactions” and the “strategies” at the meeting of “race, subjection, and spectacle” within what they call “the moment when social categories are articulated, publicized, internalized, contested, and sometimes altered” (2009: 21). This is the moment when practice theory can be brought to the forefront, and the benefits of holding the individual and social structure together are gleaned. Approaches to culture and action based on ideology, discourse, or a heteropatriarchal matrix are all brilliant expositions of how power is without center, pervasive, and often drives actions without intentions. At the same time, all three consider power to be totalizing such that there is notably little space for resistance. Yet resistance happens. Without naïvely imagining a space outside of ideology, discourse, gender, or race, practice theory offers a way to show both the possibility and difficulty of changing social structure. It affirms the earlier intuitions that the domination of power can be total, but questions whether it is totalizing.

For Hartman, this ability is the heart of the method’s utility: “practice is not simply a way of naming these efforts but rather a way of thinking about the character of resistance, the precariousness of the assaults waged against domination, the fragmentary character of these efforts and the transient battles won, and the characteristics of a politics without a proper locus” (Hartman 1997: 51). A structural account would be sufficient to paint a dire picture of the social implications of being a slave, but Hartman uses practice theory because it can recognize forms of successful resistance without triumphal congratulation of individual agency in the face of oppression. Because it brings structure and individual action together into its field of view, Hartman can use practice theory to highlight these resistances as meaningful even though they often proved futile. She writes,

Ultimately the struggle waged in everyday practices, from the appropriation of space in local and pedestrian acts, holding a prayer meeting in the woods, meeting a lover in the canebrake, or throwing a surreptitious dance in the quarters to the contestation of one’s status as transactable object or the vehicle of another’s rights, was about the creation of the social space in which the assertion of needs, desires, and counterclaims could be collectively aired, thereby granting property a social life and an arena or shared identification with other slaves. (Hartman 1997: 69)

In this key passage, Hartman begins by listing everyday practices of slaves’ struggles, and frames them with the intention of contesting slave status. This intention, however, is not about immediately destroying the large scale structures of slavery, nor realizing emancipation. Instead, the effect of those acts of resistance is to change the meaning of space. In this case, slave practices create the old space anew by subverting its inherent meaning with transformative acts of resistance. The new meaning for the space then allows for community, for collectivity, and, most importantly, for social life. It is not a space magically outside of the ideology or discourse of slavery. Prayer, love, or dance did not undo the evil denial of humanity that was slavery. In enacting those practices, however, slaves showed that the system which named them slaves was not totalizing. Instead, by reshaping social space, they resisted and wrote the meaning of human onto each other.

Looking at Hartman and others who have been successful at applying practice theory to racial identifications, it is clear that it offers a uniquely effective way to hold individuals and social structures together. Further, studies such as Feldman and Winchester’s work on school policy demonstrate that such an approach can help outline positive paths forward in the contemporary world. A practice based analysis of racial oppression would yield not only deeper understanding, but might also have practical applications. One scholar who has already developed the beginnings of such an analysis does not use an explicit practice approach. Instead, Weheliye’s Habeas Viscus is framed with assemblage theory. Weheliye aligns his use of the term ‘assemblage’ with Deleuze and Guattari, summarizing their definition of the term as “continuously shifting relational totalities comprised of spasmodic networks between different entities (content) and their articulation within ‘acts and statements’ (expression),” which “give expression to previously nonexistent realities, thoughts, bodies, affects, spaces, actions, ideas, and so on” (2014: 47). The first part of the definition focuses on the interaction between social entities and processes, but also points to the fact that those interactions require articulation through ‘acts and statements.’ Those two types of practice, one non-verbal and one verbal, form the heart of this definition. Together they express the relational interaction of various assemblages and shape or reshape both mental (ideas, thoughts) and physical (bodies, spaces) realities.

This definition shows how much assemblage theory shares with practice theory: both recognize that large, complicated, social entities are best understood by analysis of constituent parts. Both recognize that those parts are wound together and may be discursive, legal-juridical, or enacted. This is clear from Weheliye’s description of race as “a set of sociopolitical processes that discipline humanity into full humans, not-quite-humans, and nonhumans” (2014: 4). In other words, race is a system for applying full personhood to somebodies and not others. Within that system, white supremacy drives actions which give only white bodies the status of full humans.

Assemblages, like bundles of practices, are also excellent at accounting for radical change over time. However, Weheliye, unlike Hartman and others, does not offer a telling account of why the assemblages he traces persist through time. This is partially because he focuses on the assemblage at the cost of a more consistent analysis of the processes which form them. However, a generative reading of Weheliye’s work in terms of practices reveals the importance of particular acts of racialization.

To use practice theory to capitalize on Weheliye’s insight into racializing assemblages we must focus, as Orser points out, on “rehabilitating [practice] theory in such a way that assigned racial categorization is not relegated to a secondary level of stratification,” to do so, he suggests “reference to Leslie McCall’s (1992) effort to realign practice theory with gender” (2013: 146). Not only do feminist practice theorists show how to take gender from its peripheral relegation in Bourdieu, Giddens, and Schatzki, but they also tend to investigate how race, gender, and other identifications are co-constructed by practices. In addition to McCall, the work of Sherry Ortner, one of Ramsey’s key practice theoretical interlocutors, and very recently Nancy Aumais, offer ways to effect the rehabilitation Orser suggests.

Aumais admits that “practices are not directly accessible, observable, measurable or definable. Instead, they are located, hidden, tacit and difficult to describe linguistically” (Aumais, forthcoming: 10). These apparent disadvantages, however, are actually essential to the success of practice approaches. The apparent blurriness of practice, gender, and, indeed, race, changes when we follow practices to the point of individual human action. Race is difficult to define theoretically: works on racial conceptualization show that people tend to have strong opinions on what they mean when they use racial terms. Instead, what causes the apparent problem is that those meanings differ significantly from person to person, within usages over time by a single individual, and even within the perception of various listeners within a single use. But this kind of multiplicity of meaning is, as we have seen above, precisely where practice theory thrives.

By examining how linguistic and non-linguistic factors produce different meanings in different spatial and temporal contexts, a practice approach could build a detailed account of the various effects of particular meanings in different contexts. That is, practice theory is ready to look beyond the linguistic and discursive and into how various types of action contribute to racial meanings. None of these scholars have applied practice theories to explain how individual action could build its way into a system of oppression. Still, they have paved the way to a successful effort in that direction because of the key strengths of the practice approach: focus on action over individuals, on activity rather than ideation or ideology, and on exposing the processes through which activities and practice persist through time. The key to that analysis is that what someone does once is less important than doings which are repeated over time, are replicated by others, or cause organized responses. The spatial and temporal organization of activity turns what people do or say into a practice (Schatzki 2010: 77).

Let us keep this in mind as we turn back to our bus ticket purchases. Recall that we are tracing the actions of two men in the spring of 2017. Each reads about protests taking place in Charlottesville, VA in August and decides to travel from Ohio to participate. The point of this example is not to offer a definitive analysis of any of the events of the past year, which would be beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, the idea is to compare the features highlighted by a practice approach and those by a more traditional cognitive approach focused on beliefs and desires. Put broadly, because the traditional view is bound to the individual, it must squirm to involve supra-individual social entities and processes. The practice account, on the other hand, guides investigators towards essential large scale influences, like white supremacy, even if they are not obviously connected to the values or beliefs of the actor. As I shall demonstrate below, this is because it reveals that the site of action and the site of the creation of meaning are the same (Schatzki 2001).

A belief-plus-desire account of the bus ticket purchase would hinge on the idea that the two Virginia-bound men each decided to buy bus tickets out of a desire to go to the protest and counter-protest. The account might explain such desire by analyzing the ideational content of the two actors. It could continue by examining their previous involvement in protests, or their discursive production on social media. It might even manage the slightly broader demographic context of their hometowns, the socio-economic status of their families, or their religion. One would be shown to have deep connections to white nationalist ideology, and reveal the other’s ties to leftist groups. Perhaps because this account could connect those political views to upbringing or education or economic class. That can be useful, enlightening even. The brightness of those findings, however, would wash out important trends, connections and flows revealed by a practice approach.

Practice theory begins with the action, two bus tickets changing hands, and shows that the difference lies in that apparent similarity itself. Instead of building a context of cultural details, attention to action recognizes the human spatial and temporal context of the purchases. That is, reconstructing practical intelligibility by seeing what about the moment of action that made the ticket purchase feel like the right thing to do. If socioeconomic forces, political parties, or other large entities influenced the action, they must have done so by forming part of that moment’s practical intelligibility. Instead of searching for their contribution in the actor’s history, practice theory searches for it at the time of action.

I use concepts of human space and time here that were based on Heidegger’s conceptions in Being and Time (2008) and Building, Dwelling, Thinking (1993), after their development and integration into practice theory by Schatzki (2010). Put simply, perhaps too simply, human space and time are the distances of feeling: Virginia’s distance from Ohio measured not in miles, but in the imagined experience of traveling there. Virginia would, therefore, both be quite distant and in the future. If one of our bus-takers walks out of his house to the bus station, his house recedes into the past. Should he get to the bus station only to notice a forgotten wallet, that same house would suddenly jump out of the past, into the future and get nearer—nearer still if he hailed a cab for the return journey.

An important wrinkle here is that, though we are using the terms future and past and near and far, those are all descriptions of the moment of action, and not claims about what happened before or what will happen later. This is a powerful change of focus because it lets us zoom into the moment of ticket purchase while at the same time discussing temporally and spatially distant events as long as it is clear how they contribute to the practical understanding behind the action in hand.

Of course some of the important contexts derived this way would, in fact, be very similar to the ones focused on by the belief-plus-desire analysis. I might, for instance, focus on discursive Facebook activity and the socioeconomic background of the actors. But a practice theoretical frame would also show that those factors were likely quite distant from the action of bus-ticket buying. The things that were closer in human space and time would likely have been entities that would otherwise seem either too distant or too miniscule to notice. This analysis will also emphasize how much the two purchasing actions share, which, in turn, will reveal the key differences.

The first obvious spot for a practice analysis is of the shared whiteness of the actions. It might seem as though this breaks the focus on action I have been pushing for: certainly whiteness must be a quality of a person, not what they do. Contrarily, following Hartman and Weheliye shows that key aspects of race are constituted through practice. Both the white nationalist and the counter-protester, specified as white in our example, act out whiteness almost continually. Acting out whiteness is a reference to the collections of actions that make them white, both in the things that they do and for others to establish that identification and to recognize it. If they buy their ticket in person, then whiteness will be part of the entrance to the building, part of their speech, their dress, their reception. If they buy it online, whiteness will be part of the site they choose. Either way, whiteness will be part of what put the money to buy the bus ticket in their pocket.

Intertwined with the whiteness of those actions are the practices of white supremacy, practices focused on denying the personhood of non-whites. A practice theoretical construct of whiteness is a matrix of past and future happenings, including the past of slavery, Jim Crow, and Barack Obama, the present reality of mass incarceration, and, importantly, the future of an America where white people do or do not rule. Practice theory brings those things together in the moment of the bus ticket purchase, shows their presence in every instance of space-time. Actors who share the same practical understanding within the same super-temporal matrix participate in this particular whiteness regardless of their ideology or cognitive content. Even the white counter-protester, who acts with the intention to resist white supremacy, is acting from and within privilege granted by that practice, in the exact same spatio-temporal matrix. That privilege is also enacted in preferential treatment, in recognition of ability, in self-assuredness. Even having the time and money to travel and protest is a product of those privileges. However, that is not to say counter-protesters are morally equivalent to white supremacists. Just as in Hartman, their resistance still matters.

The white nationalist initially seems simpler, more aligned with beliefs and desires: he must believe his race is superior and desire its supremacy. Though we can imagine other reasons for his attendance. Perhaps he is going to impress his friends or family and thinks all of that ideology is wrongheaded. Practice theory allows for that, but, because of the focus on action, it shows that either way his ticket purchase shares its orientation with others who act out white supremacy with him. Their activity is oriented away from the recent past of a black president, and towards a future which is identified with the past. Their actions force an anachronistically and fantastically constructed practical space and time of whiteness to the fore. This enchantment is built on exemplars from the imagined past—and not just the supposedly wholesome 1950s, the decade of McCarthyism and Massive Resistance. But contemporary white nationalism pushes even further back into the past to the Klan and Jim Crow eras of de jure oppression, and back to slavery itself with White House chief-of-staff John Kelly’s comments about the Civil War. That is the logic of “Make America Great Again.”

I end by returning to Packer’s position of good and bad whites. There are certainly differences in intention among the white population, but practice theory shows that those differences are not what is important. White supremacist action has built, as Weheliye documents, practices of racialized domination which constrain and drive all white action. Contemporary white supremacy, in protests, discrimination, and microaggressions, is oriented towards creating and maintaining spaces where white action is legitimate and other action is not, where full personhood is reserved for white bodies. In such an environment, race-blind action perpetuates the practices already in place. This is abundantly clear, for instance, in school segregation. Unless designed specifically with integration in mind, school choice programs will increase segregation levels, as they have in Delaware (Niemeyer 2015), New York (Roda and Wells 2013), and nationwide (Fiel 2013). This is one of many examples that shows that truly anti-racist action by whites must not ignore race, but engage it. So far, the most effective methods have been at the policy level. The practice approach outlined above, however, suggests an important second front in the war to dispel racism. It suggests that racism and white supremacy may be supported by practices which seem innocuous. Cutting through the enchantment that seems to have trapped much of the United States requires finding those practices and ending them.

Ian Kennedy lives in Seattle where he likes biking, coffee, and not rock climbing. If possible, he looks at the water and the trees every day. As founding co-editor of Indulgence Magazine, he promotes poetry and literary analysis with emphasis on feminist and anti-racist themes. He is a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Washington where he studies how individual actions contribute to racial inequality, especially in areas of education and housing.

Works Cited

Aumais, Nancy. “Studying the doing and undoing of gender in the organisation: promises and

challenges.” Forthcoming.

Barton, Christopher P. “Tacking Between Black and White: Race Relations in Gilded Age Philadelphia.” International

Journal of Historical Archaeology. (2012) 16:634–650.

Brubaker, Rogers, and Frederick Cooper. “Beyond “identity”.” Theory and society 29.1 (2000): 1-47.

Baszille, Denise Taliaferro. “The Oppressor Within: A Counterstory of Race, Repression, and Teacher Reflection.” Urban

Review (2008) 40:371–385

Eero Vaara, Richard Whittington “Strategy-as-Practice: Taking Social Practices Seriously” Academy of Management Annals.

Jun 2012, 6 (1) 285-336

Fiel, J. E. 2013. “Decomposing School Resegregation: Social Closure, Racial Imbalance, and Racial Isolation.” American

Sociological Review, 78(5), 828-848.

Feldman, Sue, and Ilana Winchester. “Racial-Equity Policy as Leadership Practice: Using Social Practice Theory to Analyze

Policy as Practice.” International Journal of Multicultural Education (2015) Vol. 17, No. 1 pp62-81

Grootenboer, Peter, Christine Edwards-Groves, and Sarojni Choy, eds. Practice Theory Perspectives on Pedagogy and

Education: Praxis, Diversity and Contestation. Springer (2017).

Hartman, Saidiya. Scenes of subjection: Terror, slavery, and self-making in nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford

UP (1997).

Heidegger, Martin. 1993. “Building Dwelling Thinking.” Pp. 343-364 in Basic Writings, edited by D.L. Krell. San Francisco:

HarperSanFrancisco.

Heidegger, Martin. 2008. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York:

HarperPerennial.

Hopwood, Nick “Practice, the Body and Pedagogy: Attuning as a Basis for Pedagogies of the Unknown.” in Practice Theory

Perspectives on Pedagogy and Education: Praxis, Diversity and Contestation. Grootenboer, Peter, Christine Edwards

-Groves, and Sarojni Choy, eds. Springer (2017).

Hurtado, Sylvia, Adriana Ruiz Alvarado, and Chelsea Guillermo-Wann. “Thinking about Race: The salience of Racial identity

at Two- and Four-year Colleges and the Climate for Diversity.” The Journal of Higher Education, (2015) Vol. 86, no. 1,

pp127-154.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a different color. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1999).

Jörgen Sandberg , Haridimos Tsoukas in, Mir, Raza, Willmott, Hugh, and Greenwood, Michelle, eds. Routledge Companions

in Business, Management and Accounting : The Routledge Companion to Philosophy in Organization Studies. Milton,

GB: Routledge (2015).

Martin, John Levi. “What is field theory?” American Journal of Sociology. 109, no. 1 (2003): 1-49.

McCall, Leslie. “Does Gender fit? Bourdieu, feminism, and conceptions of social order.” Theory and Society 21: 837-867

(1992).

Nicolini, Davide. Practice theory, work, and organization: An introduction. Oxford university press (2012).

Niemeyer, A. “The Courts, the Legislature, and Delaware’s Resegregation: A Report on School Segregation in Delaware,

1989–2010.” Civil Rights Project – Proyecto Derechos Civiles (2014).

O’Hara, Matthew D., and Fisher, Andrew B., eds. Latin America Otherwise : Imperial Subjects : Race and Identity in

Colonial Latin America. Durham, US: Duke University Press Books (2009).

Orlikowski, W. ‘Engaging practice in research: phenomenon, perspective, and philosophy’, in Golsorkhi, D., Rouleau, L.,

Seidl, D. and Vaara, E. (Eds.): Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice, pp.23–33, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, England (2010).

Orser Jr, Charles E. Race and practice in archaeological interpretation. University of Pennsylvania Press (2013).

Ortner, Sherry B. Making gender: The politics and erotics of culture. Beacon Press (1996).

Ortner, Sherry B. Anthropology and social theory: Culture, power, and the acting subject. Duke University Press (2006).

Page, Ben, and Claire Mercer. “Why do people do stuff? Reconceptualizing remittance behaviour in diaspora-development

research and policy.” Progress in Development Studies 12, 1 (2012) pp. 1–18.

Roda, A., & Stuart Wells, A. “School Choice Policies and Racial Segregation: Where White Parents’ Good Intentions, Anxiety,

and Privilege Collide.” American Journal of Education, 119 (2013) (2), 261- 293.

Schatzki, Theodore R. Karin Knorr Cetina, and Eike von Savigny, eds. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. New

York: Routledge (2001).

Schatzki, Theodore R. 2010. The Timespace of Human Activity: On Performance, Society, and History as Indeterminate

Teleological Events. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Habeas Viscus. Durham, NC: Duke University Press (2014).

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 2010. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G.E.M. Anscome, P.M.S. Hacker, and Joachim

Schulte. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons.