Project Description

By Ian Kennedy

The houses across from and next to 2905 Garland Avenue in eastern Detroit have plywood nailed over their broken windows. According to the 2010 census, this neighborhood is overwhelmingly black. In 1925, demographics were drastically different when Dr. Ossian Sweet moved into that same house. Then, as now, Detroit’s housing was starkly segregated by neighborhoods. Invisible barriers snaked through the city, upheld by professional and social norms, which seemed to determine where black people could live. Dr. Sweet was ready to break those barriers and defend his rights. However, as the neighborhood’s first black resident, he faced an angry white mob bent on violent expulsion. After trying to defend his house, he was evicted and charged with murder. He and his family were imprisoned and put on trial. State and private violence defended Detroit’s system of racially segregated housing.

The way racial social systems in the United States were enforced changed in the 1920s. Slavery and Jim Crow were codified in law and enforced by the state. In areas where those methods were illegal, racial oppression shifted from political to hegemonic dominance. This shift did not automatically result in improved conditions for non-white Americans. Instead, oppression continued with race-neutral language to manipulate and create discriminatory legal and extra-legal systems (Bonilla-Silva, 1997, Omi and Winant, 2015). Bolstering both systems of dominance was white supremacy: a drive to establish whiteness as the only valid form of humanity through systemic denial of humanity and its attendant rights to non-white people (Smedley and Smedley, 2012). While Dr. Sweet was eventually exonerated, his ordeal reflects the rise of hegemonic white supremacy: the neighborhood mob, the police, and the prosecutor in this case collaborated on a racial project which denied Dr. Sweet’s humanity by excluding him from their community and framing him as a murderer. Importantly, historians point to the Sweet case as both a precedent for the NAACP’s legal victories of the 50s and the Black Power movement’s push for self-defense in the late 60s (Wolcott, 1993). However, that framing reinforces the myth that racial justice is progressive—that it takes time, but is consistently improving. Dr. Sweet’s victory neither arrested the growth of white supremacy in Detroit nor allowed him to enjoy his house with his family. Instead, the extra-legal battle to recognize Ossian Sweet’s humanity was lost even as he and his family were acquitted.

Fig. 1 Dr. Ossian Sweet

Historical accounts, however, cannot give us a full picture of what happened to Dr. Sweet. Theodore Schatzki’s theory of activity timespace uses conceptions of human time and space to investigate social phenomena. Applying Schatzki’s method to the Sweet case reveals more about the shared motivations and aspirations of the mob. By doing so, I uncover the way the white supremacist movement worked to create worlds where black Americans were denied personhood, even as the NAACP and Dr. Sweet won legal victories.

Detroit reacts to the Great Migration

Detroit in 1925 was a city in the midst of change. Thanks to new manufacturing jobs which came with the rise of Fordism, a strong middle class developed. Those new jobs also helped to attract a mass movement of people as part of the Great Migration. Ford’s wages far outstripped what was possible in the agrarian Southern states, so farm workers, who were mostly black, streamed north. From 1910 to 1930 the city’s black population expanded 20-fold. That growth was funneled into a neighborhood called Black Bottom in eastern Detroit. While the number of people who lived there grew rapidly, the neighborhood was geographically restricted through redlining and other discriminatory tactics (Boyle, 2004). Black Bottom became known for cramped living space, poor access to services, and poverty (Anderson, 2016).

At the same time, the black community in Detroit was developing strong institutions and community connections, a process exemplified by the opening of Dunbar Memorial hospital, founded by black doctors and focused on black patients (Boyle, 2004). Black professionals saw no reason to live in the cramped conditions which plagued Black Bottom. Instead, they sought improved housing, either moving into a small but established middle-class black enclave in western Detroit, or seeking a place in a white neighborhood. The color line, though actively constructed and vigorously defended by its white creators, had not been impermeable. Sweet’s mother-in-law lived in a “partially integrated area for many years” (Wulkovits, 1998: 28). Garland Avenue itself had at least one black-identified, though white-passing, resident: Ed Smith, who, along with his wife Marie, sold his house to Ossian Sweet. After closing the deal, Mrs. Smith assured Dr. Sweet that the neighborhood was free of the Klan activity which was increasing in Detroit, and that it would be a good place for him and his family to live (Boyle, 2004: 147). Some black doctors, lawyers, and minsters had lived in otherwise completely white neighborhoods for years.

Rather than a monolithic system of exclusion, residentail segregation in 1925 Detroit was inconsistent. Restrictive covenants, redlining, and discriminatory lending were all common and legal ways to enforce residential segregation focused on preventing people from buying or renting. Though it was legal for a real estate agent to limit black customers to certain neighborhoods, the law of the United States made it clear that people could sell houses to whomever they wanted and live in a house they owned or legally rented. As many voices in the Sweet case, most notably the presiding Judge, Frank Murphy, claimed: “a man’s home is his castle ‘whether he is white or black’” (Wulkovits, 1998: 32).

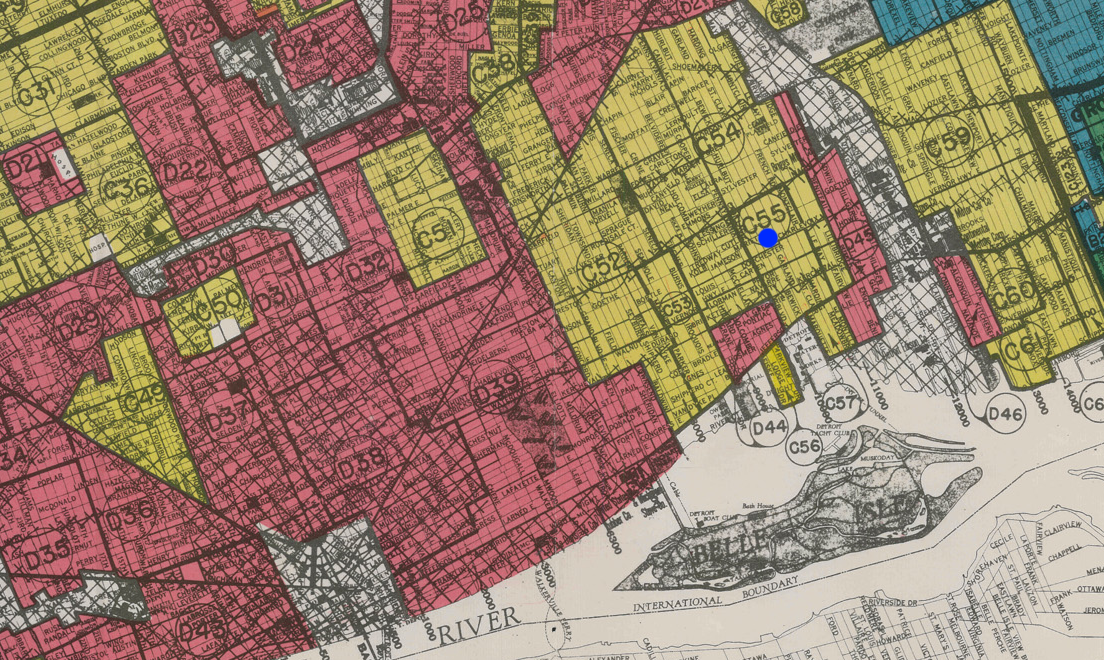

Fig. 2 Dr. Sweet’s house, marked in blue, on a 1939 Home Owner’s Loan Corporation Map.

The apparent permeability of segregation let Dr. Sweet imagine that he could move his family onto Garland Avenue, but hegemonic white supremacy’s growth would reanimate violent resistance to residential integration. Since the Ku Klux Klan came to Detroit in 1921, it steadily expanded. Apart from targeting black Americans, the Klan fed off of the fear of European immigrants, Jews, unions, and Catholics (Boyle, 2004). Eastern and southern European identifications were transitioning from racial groups to white-ethnic ones. Part of that transition was caused by an intensification of hatred, directed at the growing black urban population, especially in the North. White supremacy allowed for the unification and inclusion of white ethnics to preserve a white majority (Jacobson, 1999). Support for the Klan was mainstream. In a special mayoral election in 1924, the Klan-supported candidate, Charles Bowles, would have won if not for seventeen thousand ‘misspelled’ ballots that went uncounted (Boyle, 2004: 143). It is unsurprising then, that Detroit in 1924 and 1925 saw cross-burnings, unruly chanting mobs, rallies fifty-thousand strong, and increasing racial violence.

In the summer before Dr. Sweet moved into his new home, at least three other black families faced violence as they entered new neighborhoods. Just one street outside of Black Bottom, mobs throwing stones attacked Fleta Mathies. Mathies had recently arrived with her family from Georgia and was defiant and unafraid in the face of the attacks (Boyle, 2004: 152). After a rock broke her window as she slept, she defended herself by firing a sidearm into the street. She was arrested, but eventually acquitted. A medical colleague of Dr. Sweet’s, Dr. Alexander Turner, moved into a house on Tireman Avenue. Led by the Tireman Neighborhood Association, a mob pillaged Dr. Turner’s house and stole his deed at gunpoint. He barely escaped with his life. Vollington Bristol, both Dr. Sweet’s friend and a black homeowner in an otherwise white neighborhood, was attacked by an armed mob so large it took “two hundred or more” police to disperse it (Boyle, 2004: 154). All of the aggressors in each of these three cases were white, and despite the clear criminality of their actions, no white person was arrested or charged.

While racial violence was not new to Sweet—in fact witnessing it was formative for him—these reactionary attacks changed how he felt about moving to Garland Avenue.

Broken Glass on Garland Avenue

By the time he moved into his house on the night of September 9th, Dr. Sweet expected to face violent resistance. He knew Dr. Turner and Bristol personally and no doubt had read about Mathies’s plight. Dr. Sweet had no intention of yielding his property. He brought friends, guns, and extra food, arraying them throughout the house to repulse attacks and prevent flanking maneuvers (Boyle, 2004: 164). These preparations suggest that Sweet was ready for a violent siege. If he showed he could not be cowed, perhaps he would be able to hold on to his home and build a life there, if not gain the love of his neighbors.

His neighbors, however, made some of their own preparations. Influenced, and partially organized by, the Tireman Neighborhood Association and the KKK, Garland residents organized their own neighborhood association. This group held rallies and sent block captains around to houses to encourage residents to include restrictive covenants in their deeds (Boyle, 2004). Short of actually planning an attack on his house, the Neighborhood Association made clear that their vision of a neighborhood was one which did not include black residents.

The first night in the new house was relatively, perhaps surprisingly, quiet. A few police officers stood outside, some people from the neighborhood walked by, and the night passed without incident.

The next day, however, a larger group formed out on the street. More police were dispatched, and the crowds and traffic were thick enough that officers stepped in to organize the flow of people. While there was mumbling and some shouts from the crowd, there was no obviously violent speech or action until Ossian’s brother Otis Sweet and his friend William Davis arrived in a taxi. Accounts agree that at this moment people yelled “There’s the niggers, get ‘em” and the crowd became a mob (Boyle, 2004: 37). Sweet and Davis ran from the car to the house under a hail of stones and objects. Inside, the Sweets were preparing for dinner and were surprised by the eruption. The mob flowed around back to attack, so Sweet activated his defense plan, taking arms to the back of the house and sending his friends upstairs to wait and watch.

The police, meanwhile, stood by inactive. They could not avoid seeing that the house and its occupants were under threat. Like Dr. Sweet, they knew what had happened to Turner, Mathias, and Bristol: all attacked by armed white mobs. They knew that those attacks often moved black homeowners out of legally purchased property and endangered lives. Also, the Klan influence in Detroit had infected the force; the officers would be severely partial to the violent assailants (Boyle, 2004).

As the trickle of rocks grew into a torrent, the first window at 2905 Garland shattered. Here, moving into a neighborhood not expecting welcome, but tolerance, Dr. Sweet instead faced hundreds of angry and violent would-be neighbors. He had made his way north from a home state terrorized by lynching through a country steeped in racial violence (Anderson, 2016). He later testified in his own defense: “I realized in a way that I was facing the same mob that had hounded my people through its entire history. I realized my back was against the wall and I was filled with a peculiar type of fear—the fear of one who knows the history of my race” (Wukovits, 1998: 30). When the second window broke, scattering shards of glass into the home, a shot rang out, possibly from the street, possibly from the house. The Sweets and their friends opened fire—in a legally sanctioned defense of their home—firing ten shots and dispersing the crowd. Two members of the mob were hit. Eric Houghberg was shot in the leg but recovered. Leon Breiner, a factory foreman who lived nearby, later died.

The police, who had been idle, sprang into action at the sound of the shots. They rushed into the house, arrested and jailed its occupants, and charged them with murder. In the two trials to follow, the Detroit police and prosecution flagrantly manipulated evidence, encouraged perjury, coaching tens of witnesses to say that only a few people were gathered on the street. After an initial hung jury, all defendants were acquitted or had their charges dropped. Held for weeks before trial, prison conditions left Dr. Sweet’s brother, wife, and daughter with tuberculosis, from which they all died (Anderson, 2016). While he went home and fixed his windows, Dr. Sweet struggled to pay off his mortgage. Eventually, he lost the house and moved to Black Bottom. He died there by his own hand in 1960.

Historical accounts of Sweet’s ordeal often emphasize his trial and its long-term impact on the legal progress of the Civil Rights Movement. The NAACP hired Clarence Darrow of Scopes Trial fame. That partnership was effective in the Sweet case, and thus undermines a flawed narrative that the movement began in 1954, showing instead that “thirty years before Brown v. Board of Education, the NAACP was directly challenging both legal and extra-legal attempts to draw a color line in American towns and cities” (Wolcott, 1994: 26). It also highlights the continued legal and extra-legal oppression of black Americans in the early 20th century.

Focusing on the legal action suggests that the Sweet case should have set a precedent that black families had the right to move into white neighborhoods and defend their houses, with violence if necessary. That was, and is, certainly the right conferred to any person who owns a house in the United States. Instead, the result of the Sweet case, and especially the eventual deaths of Dr. Sweet’s family members, emphasized the divide between legal and social process in the United States. While Dr. Sweet was eventually exonerated, residential segregation in Detroit, and the country, carried on. A key instrument of that segregation, racially restrictive covenants, were upheld as legal in the Corrigan v. Buckley less than a month after the Sweet trial. One possible way forward is to look more deeply at those factors which undergird social action. Considering the mob violence directed against Dr. Sweet as activity lodged in a particular temporal and spatial context allows for this investigation.

Theoretical Framework

Timespace is a way of talking about human activity pioneered by Theodore Schatzki. In his book The Timespace of Human Activity he introduces a practice-theoretical conception of human action based on the social theory of Pierre Bourdieu and Anthony Giddens and the philosophy of Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Timespace is a unified way of considering the temporal and spatial aspects of the human lifeworld. It is, Schatzki argues, “a central constitutive feature of human activity” (Schatzki, 2010: ix). This contrasts with traditional views of why people do what they do because it does not assume that people act according to their desires. In other accounts, like that of Donald Davidson, people choose the course of action which will get them what they want based on what they believe about the world (Schatzki, 2010: 123). In that logic, first there are beliefs, then desires, and then action.

In contrast, Schatzki’s timespace is linked to the immediacy of experience. What people do, in this conception, comes from the human time and space in which they act. A full understanding of the time of an action requires an understanding of the space of that action. On that basis, Schatzki argues that the two dimensions should be considered together as timespace (Schatzki, 2010).[2]

Human space is focused on the accessibility of places through paths. On his rounds at Dunbar Memorial Hospital, Dr. Sweet was focused on the patients he needed to visit. The path to their rooms was present for him, even as it wound its way through the building. If, midway through rounds, a colleague had asked him to make an extra stop to pick up some files, that path and its places would have changed. The records room, previously unimportant, would have entered Dr. Sweet’s concern, that place and the hallways leading to it showing up in a new way.

Human time is defined by what aspects of the future or past obtain on present activity. The first time Dr. Sweet boarded one of Detroit’s ubiquitous streetcars, it might have felt awkward. Like anyone dealing with a new public transportation system, he lacked the relevant past to guide his activity. He would have been forced to carefully think through the process of buying a ticket and finding the right entrance. As he used the system more, though, the process would eventually require no thought. In both cases human past—experience or its lack—influences activity. Human futures also affect activity. Each time Dr. Sweet used a streetcar, it would be for some purpose, usually getting to a place, but perhaps also being with a person, exploring, or wasting time. Those are all states of the world for the sake of which he could board, and each would lead to a different experience. They are the future of his activity.

Human time and space are always integrated in timespace. On the streetcar the spatial orientation towards which Dr. Sweet moves is aligned with a future for the sake of which he acts. Each of the other passengers, though sharing the now of riding the streetcar, has their own orientation, past, and future guiding their activity. As passengers, their timespaces are interwoven, but not the same. Activity has a towards-which even when it is almost immobile. Seated meditation, for instance, is just as spatially oriented, in its stillness, as streetcar riding. The towards-which, then, is simply the same place in which the meditator is already.

What binds space and time together is their co-reliance of meaning, formed by the teleological, or purpose-focused, nature of their connection to human activity (Schatzki, 2010: 37). This telos is manifest in the spatial and temporal orientation of human actors. We are always oriented towards a place, even if that place is where we already are, and towards a future, which is the state of the world for which we act.

Moving into a new house, as in the case of the Sweet family, shows how the time and space of the activity are only fully understood teleologically in terms of one another. The family might have acted for the sake of many different futures when they purchased their new home: having more space for a growing family; wanting a property in line with increased status and wealth; living comfortably. All of those create their meaning, at least partially, spatially. Property status is connected to whatever the location gives the owner access too, and what the neighborhood means to the owner and their friends. Living comfortably has to do with the proximity of amenities, family, friends, and, perhaps, enemies. Making a home space for family is essentially providing a place towards which relatives can turn.

Finally, timespace is not a quality of individual actors, but of activity itself. People do not have timespace, they perform activity which is made up of timespace. Therefore, people, especially when they act together, share timespace.[3] For instance, when a person moves into a new neighborhood, the people who live there already share the timespace of having a new neighbor. That gives them, suddenly, a shared past and shared orientation—towards the newcomer’s house—which might spur them to similar actions, like buying housewarming gifts, organizing a welcoming party, exchanging contact information, or forming an angry mob—depending on their previous conditioning.

The Timespace of Ossian Sweet and his Attackers

Dr. Sweet’s move into a new home shares a similar timespace with most housewarmings. He acted for the sake of futures like providing a safe home for his family and living in a house worthy of his station. Those futures changed after the attacks on Turner, Mathies, and Bristol. Sweet kept acting for the sake of living in a house in line with his status and wealth. He kept acting for the sake of providing his wife and daughter with the kind of life they deserved. His pasts include his experiences with racial violence: traveling in Europe and seeing the possibilities for life there; living with his mother-in-law’s family and feeling shame at not having his own place; being trapped by the conditions of Black Bottom. These are futures and pasts which he shared, I believe, with other people who moved into new houses in that time and place.

However, as Sweet learned more about the risks of his move, he added possible futures: futures of ensuring safety against people who might wish him harm. He allied himself with the NAACP and its representatives. The threat of violence also activated certain parts of Sweet’s past: lynchings he saw as a boy, the Red Summer of 1919, and the ethnic cleansing of his family’s town in Florida 1920 (Anderson, 2016). Suddenly, the whiteness of the new neighborhood was more salient, the possibility of Klan members nearby more relevant. With that past resurfacing, the Deep South was suddenly closer than it had been in years. Detroit and Florida were brought together by their shared racism and white supremacy. That peculiar fear, which perhaps Sweet had not felt so acutely since coming north, began to sneak back into his life.

This analysis emphasizes how Sweet’s battle was intertwined with the battle other black Americans faced, partly because they faced similar dilemmas in the present, like being the object of racial violence. Sweet also shared the past of the experience of lynchings with many others who, thankfully, might not have suffered violence themselves.

In the timespace of Dr. Sweet’s house moving activity, his true humanity finds full expression. He owns a house, he hosts guests, he has a family and a job. His past experience of violence looms with possible threats to his life, but not to his humanity. Until, that is, he feels the peculiar fear.

Across Sweet’s property line stood the white rioters who had very different pasts and acted for the sake of very different futures. Though only meters away, their timespace was separate from Dr. Sweet’s. In resisting their neighborhood’s integration, they were engaged in a white supremacist racial project—not that they were all members of the Klan or harbored more prejudicial thoughts than other white Detroit residents. Instead, the timespace of their action was tainted by white supremacy: not as an ideology, but built into their motivation and orientation. White supremacy shaped their pasts, the future they imagined for their neighborhood and city, and the spatial orientations of those pasts and futures. Threaded through the timespace of their activity, white supremacy denied the humanity of Dr. Sweet by reducing him not even to an unnamed black man, but a dangerous specter of blackness. This is true whether or not the residents of Garland Avenue were Klan members, whether or not they were prejudiced, whether or not when they saw Dr. Sweet they saw a man.

Let’s begin with the pasts of the people who made up the mob. While the neighborhood was not a wealthy one, owning a home there was still difficult. Mortgage payments loomed and salaries were not high, a past of struggle that was spatially located in the neighborhood (Boyle, 2004). Until Dr. Sweet moved in, they believed that only white people lived and should live in their neighborhood. White supremacy enforced the racial makeup of the neighborhood, which provided status for the area. These were issues brought up at the neighborhood association meetings and again by the block captains on their rounds.

It is likely that none of the mob participants ever had a close relationship with a black person. Whether this is obvious or not, that means that their actions oriented towards black people were entirely motivated by hegemonic white supremacy: cultural representations of black folks in media, talk on the street and in drawing rooms, and the stereotypes that talk enforced. This hegemony included attitudes towards black residents and black neighborhoods. Whether they had been to Black Bottom or not, they certainly knew it by reputation: dirty, poor, cramped, violent. Dr. Sweet would have been seen at least partially as a representative of that neighborhood and its reputation.

The expulsion of Dr. Turner and the attacks on Bristol and Mathies were important and present in the minds of Dr. Sweet and the police, but also part of the pasts of the people in the mob as well. Another important shared past of many of the people in the mob was that they attended the neighborhood association meetings that took place in August. This was a direct connection of white supremacist organizations, including the KKK, with the events of September 9th. Even if they were not members, people in the mob had been to one of those meetings or rallies, and visited by block captains whose talk was focused on the new situation in the neighborhood. Such experience made up the past of the people in the mob.

The future that the mob worked for the sake of was maintaining an all-white neighborhood. The meaning of that all white neighborhood was set in opposition to Dr. Sweet as a representation of Black Bottom. The orientation of all of this future was towards Garland Avenue in general and Dr. Sweet’s house specifically as the site of the possible downgrade. Those are real differences between neighborhoods, but the shape of the relationship between them, and their definitions as white and black neighborhoods, was still constructed by white supremacy.

Together these pasts and this future built a version of Dr. Sweet and his house which denied his humanity. He was instead an embodiment of a neighborhood, a threat to a future, the focus of neighborhood association meetings. It was in the face of that attitude that Dr. Sweet’s fear was peculiar. He saw himself as facing a mob that represented “the same mob that had hounded my people through its entire history,” a mob that came not for his life, but for his existence as a person.

Conclusions

Dr. Sweet’s integration of Garland Avenue was a clash of two social timespaces. In one, Ossian Sweet had the legal rights of any other American person. Though he understood that the justice system would not punish white aggressors, he believed he would be able to defend land that he owned. He was also acting for a future in which other non-white people, perhaps without the status he enjoyed, would be able to live wherever they wanted. On the other hand, the timespace of his neighbors was constituted in a different world. Here, burgeoning white supremacy struggled to undermine the rights of black Americans by force. In this world, black people did not have the right to live outside of a ghetto, regardless of their profession, wealth, or status. They did not have the right to defend their property against attack. Looking at the violence Dr. Sweet faced in terms of conflicting timespace also makes the outcome of the trial and the subsequent lack of progress make more sense. With strong legal representation and clumsy opposition, the NAACP mounted a successful defense. However, in the absence of a national movement to remake or join the divided timespaces, housing segregation remained not only acute, but legal.

Social justice movements have been successful at challenging legally sanctioned discrimination. However, in the contemporary United States, systemic racism still drives practices of residential segregation, disproportionate police violence, and economic inequality. Ossian Sweet’s ordeal teaches us, sadly, that legal victories may not be enough to dismantle those structures. Instead, we must bolster legal efforts with a clear understanding of the pasts, futures, and orientations which drive racist practices. We need to engage with the timespace of oppression, so that we might find ways to catalyze its undoing.

About the Author:

Ian Kennedy likes reading, writing, and talking. He thinks the most important problems we face today are ones we haven’t even begun to face, and aims to reorient discourse towards them. In his piece, Dr. Ossian Sweet faces the glass walls of residential segregation. Though Dr. Sweet made his way past those barriers almost a century ago, residential redlining persists today.

Works Cited

Anderson, Carol. White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. Bloomsbury, 2016.

Bonilla-Silva. “Rethinking Racism: Toward a Structural Interpretation.” American Sociological Review, Vol. 62, No. 3. Jun. 1997, pp. 465-480.

Boyle, Kevin. Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Rights, and Murder. Henry Holt and Company, 2004.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Harvard University Press, 1999.

Omi and Winant. Racial Formation in the United States. Routledge, 2015.

Schatzki, Theodore R. The Timespace of Human Activity: On Performance, Society, and History as Indeterminate Teleological Events. Lexington Books, 2010.

Smedley and Smedley. Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview. Westview Press, 2012.

Sullivan, Patricia. Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement. The New Press, 2009.

Wolcott, Victoria W. “Defending the Home: Ossian Sweet and the Struggle against Segregation in 1920s Detroit.” OAH Magizine of History, Vol. 7, No. 4, Summer 1993, pp. 23-27.

Wukovitz, John F. “`This Case Is Close To My Heart.’.” American History 33.5 1998, pp. 26-32,66,68.

Image Credits

Fig. 1 Taken by Ian Kennedy 2016

Fig. 2 Fair use from Wikipedia

Fig. 3 Taken from Michigang Radio.org: http://stateofopportunity.michiganradio.org/post/see-maps-1930s-explain-racial-segregation-michigan-today

[1] Both Anderson and Boyle document Dr. Sweet’s experience witnessing racial violence in youth. Boyle writes that when Fred Rochelle was lynched in Dr. Sweet’s hometown of Bartow, Florida, it was “the most terrifying moment of [Dr. Sweet’s] young life” (Boyle, 2004: 69).

[2] Timespace is not truly a feature of beings, but of activity.

[3] Schatzki’s account of timespace actually outlines three ways more than one person can have partially overlapping timespace: common, shared, and orchestrated. For the purposes of this paper, only shared timespaces, when individuals act in light of a shared past, for the sake of a shared future, or oriented in or towards a shared spatiality, will be considered.